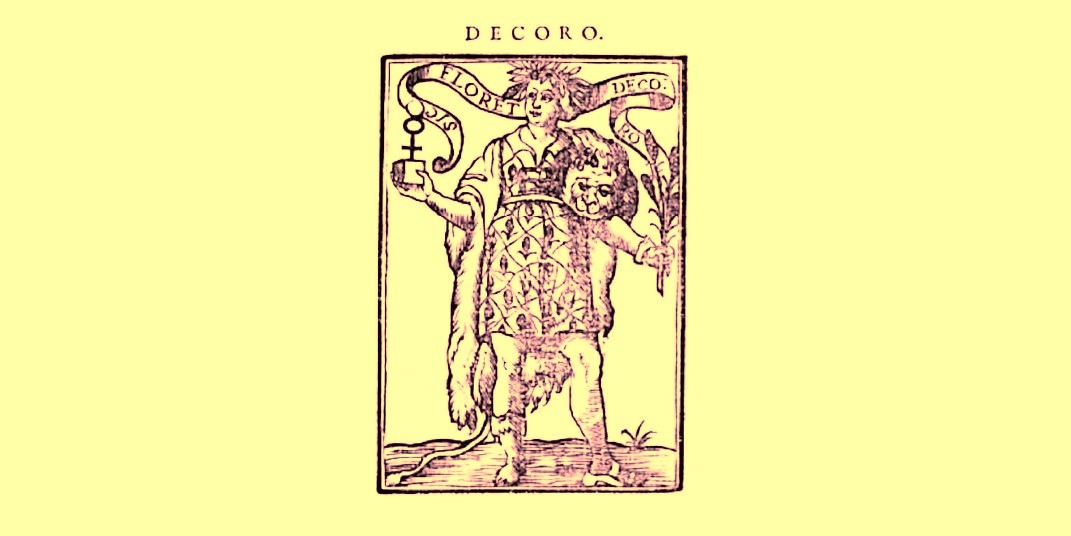

by Cesare Ripa, Giovanni Zaratino Castellini

After Youth, Beauty and Lion's fur, god Mercury's symbol is the fourth attribute of Decorum we encounter when reading the entry compiled by Giovanni Zaratino Castellini for Cesare Ripa's Iconologia. The object, having for its base a square - today we would say a cube - is found in the right hand of the personification of Decorum, reproduced in the 1613 edition of the Iconologia and later editions. The ideogram of Mercury has a tripartite structure, which is the sum of the three symbols - the cup, the circle and the cross - relating to the Moon, the Sun and the Earth. It is thus the synthesis of the three essential archetypes contemplated in astrology: the feminine, the masculine and the material substratum. Also important is the role attributed to mercury in alchemy, where, together with sulphur, it is the primordial element present in every other metal. Among the various historical anecdotes that Castellini recalls drawing on his classical culture, there is one concerning fine arts, in which the Greek painter Zeuxis sarcastically apostrophizes Megabizus when the latter, inexperienced in painting, makes some incautious comment. See C. Ripa, Iconologia, Eredi di Matteo Florimi, Siena 1613, pp. 173-174.

The square with the sign of Mercury indicates gravity, stability and constancy in speaking according to decorum, which is why Mercury was called Tetragonos by the Greeks, i.e. firm, stable, prudent, because we must not be imprudent, varied and changeable, overstepping the boundaries of decorum, nor must we attack and blame people, despising their feelings, because this is arrogance and debauchery, but we must show reverence towards all, as M. Tullius advises, speaking of decorum as moderation in deeds and words. Adhibenda est igitur quadam reverentia adversus homines, et optimi cuiusq; reliquorum. Nam negligere, quid de se quisq; sentiat non solum arrogantis est sed etiam omnino dissoluti 〈1〉. Let us bear this in mind when we speak respectfully of others: for he who speaks well and respectfully is a sign that he is a benevolent and honourable man; he who speaks badly is a sign that he is an evil, malicious, envious and unhonourable man, like, according to Homer 〈2〉, Thersites with a forked tongue, fickle and always ready to slander and speak ill of his king; Ulysses, on the contrary, is taciturn and thinks before he speaks; when he speaks, he is calm and eloquent, and prudent, knowing, as a wise and prudent man, that for the decorum of the wise man, the tongue must not be quicker than the mind, for one must think well before he speaks. Linguam preire animo non permittendam. Chilon of Sparta 〈3〉 said, that one should think very carefully about it, because speaking is an indicator of the soul, according to how one speaks with decorum, & therefore the Greeks used the expression Aνδρός χαρακτήρ Hominis character 〈4〉. Mark of man, as reported by Pierio Vittorio in Varie lettioni lib. 9. cap. 6., for as the race of animals may be recognised by the mark, so by the manner of speaking one may tell what nature, & condition men are 〈5〉. Greek moral philosopher Epitectus said in the Enchiridion; Præfige tibi certum modum, & characterem, quem observes, tum solus tecum, tum aliis conversans, operam da ne in colloquia plebeia descendas sed, siquidem fieri potest, orationem tranfer ad aliquid decorum, sin minus, silentium age. I.e. observe a behaviour or a character that is practicable in private, when conversing with others in public, do not fall into vulgar discourse, but as far as possible try to speak on subjects of decorum, otherwise keep silent. 〈6〉. Let us respect decorum in speech, let us speak reasonably of others, and let us not speak ill of anyone, but rather praise him, and let us avoid blaming the work of other men, especially those who are not of our own trade or profession. For many are accustomed to pass judgement on all things, by which they betray their ignorance, and that with little decorum, as did the Prince Megabizus, who, in the house of Zeuxis, found fault with some figures, and reasoned with the pupils of Zeuxis about the art of painting, to which Zeuxis replied; When you held your peace, these boys admired you as a prince clothed in purple, but now they laugh at you, because you want to reason about an art that is not your own 〈7〉; we shall be even more obedient to decorum in speech, if we reject ugly and deceitful words, and speak of honest and honourable things, which is especially fitting for young men of fair countenance, for to the beauty of the body belongs the beauty of manner. For this reason the philosopher Diogenes, seeing a handsome young man speaking without decorum, said to him: “Are you not ashamed that you draw a leaden knife from such a beautiful ivory scabbard?” Meaning by the scabbard, the beauty of the body; and by the leaden knife, his unmannerly indecent speech, as lead among metals, see Diogenes’ Life by Diogenes Laertius, where he says. Videns decorum adolescentem indecore loquentem, non erubescis ait, ex eburnea vagina plumbeum educens gladium? 〈8〉.

〈1〉 «We should, therefore, in our dealings with people show what I may almost call reverence toward all men - not only toward the men who are the best, but toward others as well. For indifference to public opinion implies not merely self-sufficiency, but even total lack of principle». Marcus Tullius Cicero, De Officiis, liber I, 99 [ed.]. 〈2〉 According to Homer; Castellini refers to Iliad [ed.]. 〈3〉 Linguam preire animo non permittendam: 'The tongue must not take precedence over the mind'. Chilon of Sparta (c. 600-520 BC) is remembered as one of the Seven Sages of ancient Greece [ed.]. 〈4〉 Aνδρός χαρακτήρ Hominis character: 'The character of man', concept derived from the philosopher Theophrastus and the playwright Menander, exponents of the Greek-Hellenistic culture of the 4th-3rd century B.C. [ed.]. 〈5〉 Castellini refers to Variae Lectiones (1569) by the Florentine philologist and humanist Pietro Vettori (1499-1585) [ed.]. 〈6〉 Epictetus (c. 50-130 A.D.), Greek philosopher, author of the Enchiridion, from which Castellini draws the Latin quotation and subsequent translation [ed.]. 〈7〉 The anecdote of the meeting between Persian prince Megabizus and Greek painter Zeusi is reported in Suda (or Suida), a 10th century Byzantine encyclopaedia [ed.]. 〈8〉 Castellini quotes the Life of Diogenes of Sinope included in Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Philosophers, VI [ed.]. Homepage; "Decoro", graphic elaboration of the table illustrating Cesare Ripa's "Iconologia" in the edition published by Pers, Amsterdam 1644. Below; reproduction of pages 173-174 from Cesare Ripa's book, "Iconologia", Eredi di Matteo Florimi, Siena 1613 (www.archive.org).