by Sara Palestra

Adeline Harris: biographical outline

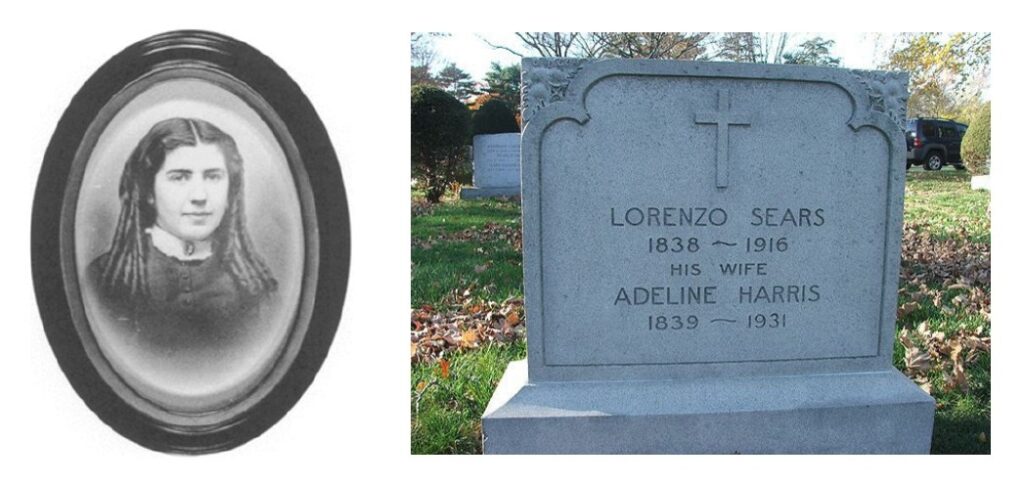

As with so many other American quilters active in the 18th and 19th centuries, information on Adeline Harris (1839-1931) is not abundant, but in her case it gives a sufficiently clear picture of her life and art. Much of it comes from Harris’s own diaries and the accounts of family members and descendants 〈1〉.

Born on 7 April 1839 in Arcadia, Washington County, Rhode Island, Adeline Harris was the third and last child of James Toleration Harris (1806-1895) and Sophia Amelia Knight (1812-1887). Her older brother and sister were George Harris (1833-1875) and Eleanor Celynda Harris (1835-1897). Thanks to her father, a textile industrialist, the family enjoyed a wealthy economic status and Adeline’s education took place mainly at home with private tutors. But her studies also included a few months of private schooling and three years of boarding school, including two at East Greenwich Academy, a prestigious Methodist institution in East Greenwich, Rhode Island, and one at a girls’ school in New London, Connecticut. Compared to most of her peers, Adeline was able to receive a thorough education, and in her memoirs, her great-granddaughter Amey Howarth Mackinney remembers her as a brilliant student 〈2〉.

In 1866, Adeline married Lorenzo Sears (1838-1916), an Episcopalian priest. Her decision to marry not an entrepreneur and businessman (like her father) but a member of the most educated segment of society, the clergy, confirmed Adeline’s belief that cultural and spiritual values were now taking precedence. Her husband had a distinguished career. A graduate of Yale, he was a professor of rhetoric and literature at the University of Vermont (1885-88) and at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island (1890-1903), before devoting himself entirely to literary studies.

Satisfied with the fame she had achieved through the most important of her quilts, the Autograph Quilt, which we will discuss in a moment, Harris lived a long and quiet life. She had four children, only one of whom, Sophie Harris Sears (1872-1949), reached adulthood. He lived until his death on 10 May 1931 in Providence, in a residential area near the campus of Brown University.

Signature Quilts

In the Anglo-American tradition, Signature Quilts are those bearing the autograph signatures (in which case they are also called Autograph Quilts), or embroidered or stamped signatures, of several people 〈3〉. Although there are older examples, they were particularly popular in the 19th century as a means of raising funds or as a memorial to families who had decided to leave their place of origin and emigrate to the west of the country to build a new life in the frontier areas. The commemoration of historical and community events or the listing of affiliations to organisations and groups of various kinds were other possible reasons for their creation. A valuable resource for genealogical research, Signature Quilts rarely include the signatures of famous people, and Adeline Harris’s falls into this narrow category.

In the second half of the 1950s, while still a student, Harris began to design a large quilt with features that were anomalous to the predominantly utilitarian tradition of quilting. The resulting image of Harris is that of an educated yet creative woman, consciously rooted in the romantic culture of the time, with the mystical and transcendentalist overtones typical of American culture.

At the time, the practice of collecting autographs was very much in vogue, particularly for its spiritual and cognitive implications. It was widely believed that an individual’s signature revealed the most salient aspects of their personality, and that those who possessed the autograph could better discover and emulate his most outstanding traits. As early as 1835, the women’s magazine “Godey’s Lady’s Book” began publishing pages reproducing the signatures of distinguished American citizens and displaying them for public admiration. By the 1850s, collecting signatures had become so popular that newspapers published articles illustrating the magical significance of exchanging autographs and the act of signing itself as an expression of respect and esteem. Autograph collectors met regularly to comment on and exchange the pieces in their possession. They created a precise community space that identified them with an intellectual elite.

To collect autographs for her quilt, Adeline wrote directly to those interested, outlining the project. The envelope contained a piece of cloth which, once signed and returned to Mrs Harris, would be sewn into the quilt. Although this was the predominant method, it is likely that Adeline knew some of the illustrious individuals selected for her project personally. Prior to the outbreak of the Civil War (1861-65), the entire Harris family had resided in Washington D.C., where James Toleration Harris had a close network of relationships with officials. It was through these relationships that Adeline was able to personally approach President Lincoln and, as we read in her great-granddaughter’s family memoirs,

«She danced with Abraham Lincoln at his Inaugural ball, and we still have the silk damask from which her ball gown was made. [She was] an ardent admirer of Abraham Lincoln. She bought, and read, every book practically, that was written about him» 〈4〉.

Adeline’s admiration for Lincoln explains her tendency to collect autographs from people who shared the president’s political views. Many of the senators, congressmen and governors included in the quilt were militants in the newly formed Republican Party, while others, albeit from more moderate positions, opposed the secession of the southern states that sparked the Civil War.

Description and history

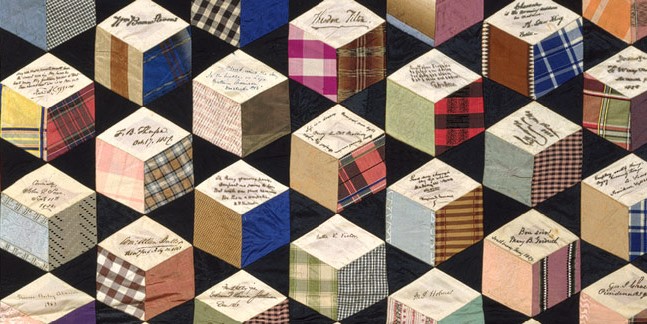

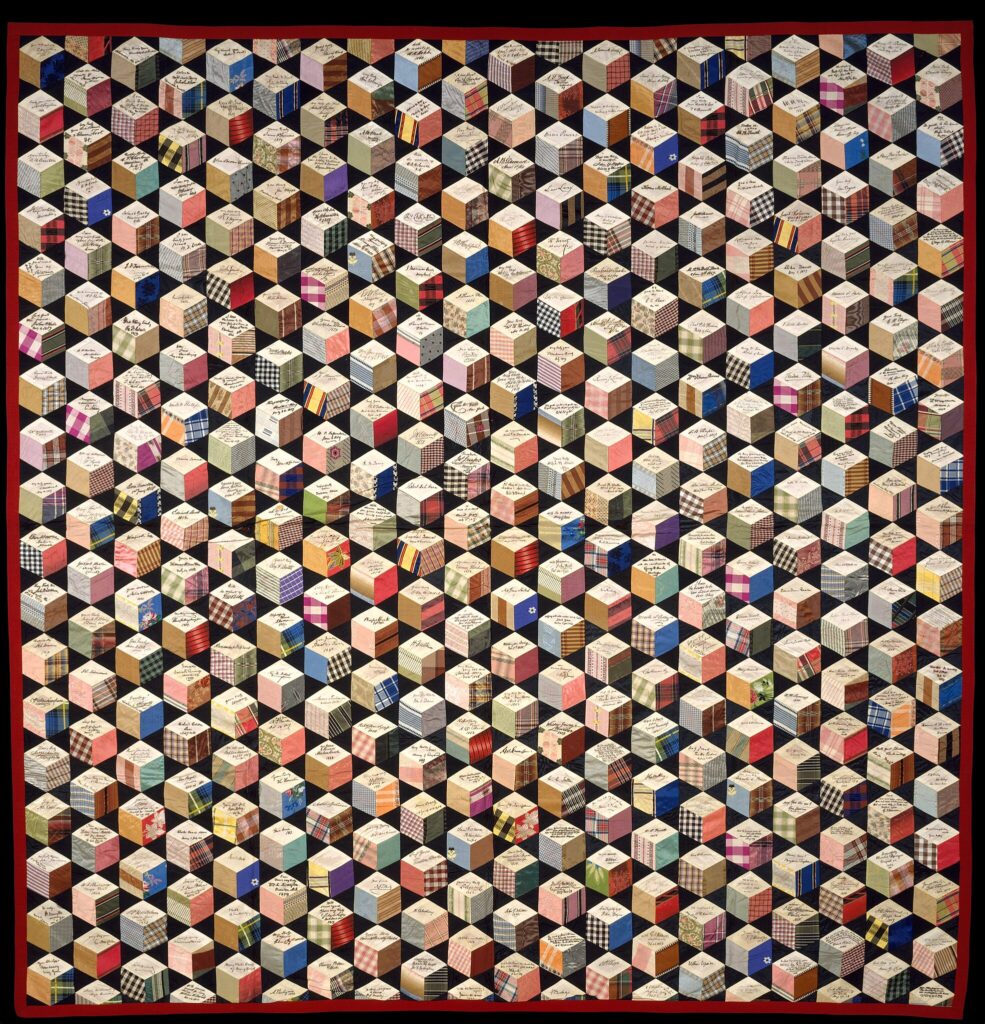

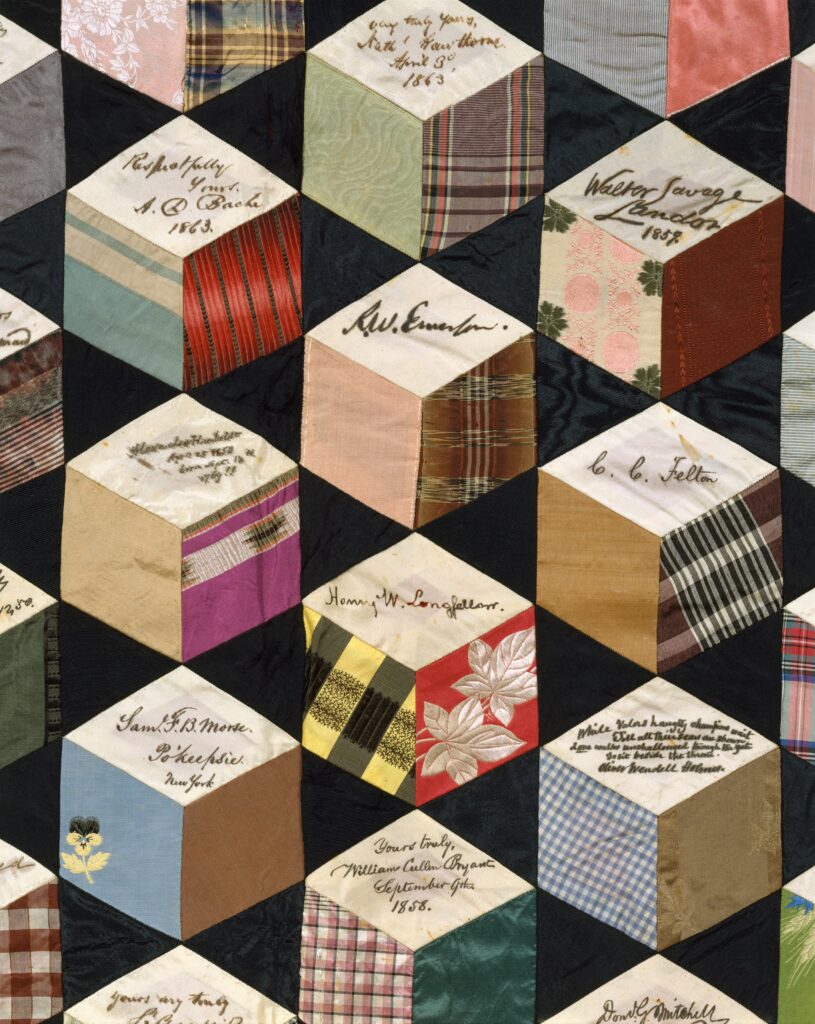

Adeline’s most important work began in 1856 when, at the age of seventeen, she began sending letters to people she admired, asking them to autograph the piece of silk in the envelope. When the signed pieces of fabric were returned, they were sewn together by hand, one by one, according to a compositional criterion known as Tumbling Blocks. This pattern, also known as cubework, consists of diamond (i.e. rhomboid) and triangular cut-outs. The use of coloured silk, the black background and the way in which the various pieces are strategically assembled create a trompe l’oeil with a three-dimensional effect, known since Greco-Roman antiquity as a floor mosaic, of a succession of cubes whose three faces are visible 〈5〉.

Each block is made up of three rhomboid-shaped pieces of fabric: one of white printed silk, which forms the top of the cube, and two of coloured or decorated fabric, which correspond to the sides. The spaces between the blocks are filled with triangular cut-outs in black silk. The quilt is made up of three hundred and sixty staggered blocks, corresponding to thirty-six horizontal rows and twenty vertical columns.

Examination of the seams in the upper part of the work has made it possible to reconstruct their exact sequence as Harris executed them. First, the diamond-shaped pieces were mended to form a cube, then the cubes were joined to form columns, and finally the columns were stitched together across the width of the quilt. In total, Adeline cut and sewed about one thousand eight hundred and forty pieces of silk. It is thought that most of the silk used was imported from Europe, but American silk, particularly monochrome silk, may also have been used. The quilt incorporates the various pieces of fabric in a seemingly random manner. Often the artist would use the same fabrics in several blocks, but would never repeat exactly the same combination of fabrics: a methodical distribution designed to create a harmonious effect. Traditionally, quilts were made using scraps and remnants from previous sewing projects, or by salvaging fabrics from unwanted garments. Some of the fabrics in Harris’s work were probably taken from parts of dresses or hats, as evidenced by the presence of stains and signs of wear.

The brilliant colours of the quilt are still in excellent condition today, given the natural origin of the dyes used in the fabrics. Bright pinks, reds and indigo blues are among the most common colours, with other combinations of dyes tuned to purple, yellow, green, brown and black. Pink, being very sensitive to light, has suffered from fading over time, but this has not resulted in significant changes.

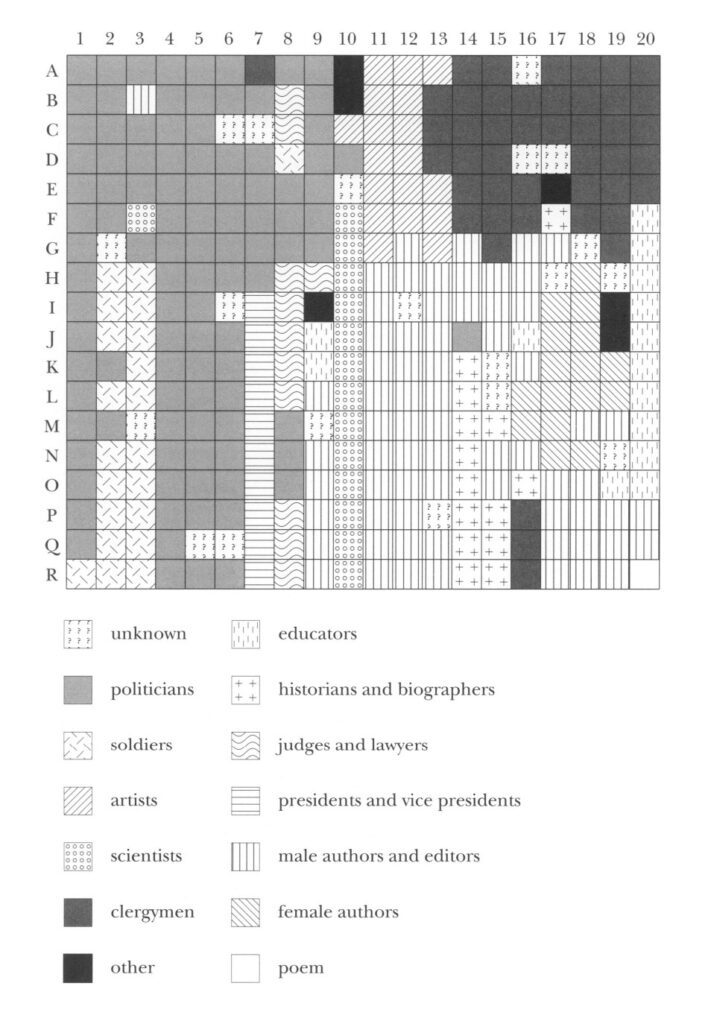

Fine-tuning her composition programme, Adeline decided to group the names of the characters according to their professions. It was then possible to draw up a diagram visualising the distribution of signatures in the different parts of the quilt. In a nutshell, these are the different types of personalities: politicians and writers are the most numerous groups, but there is no shortage of soldiers, scientists, clergymen, educators, historians and biographers, judges and lawyers, as well as some unidentified personalities.

Adeline worked on his project for a long time, collecting autographs until 1863, although the last signature dates from 1867. However, the placement of the signatures of Vice Presidents Schuyler Colfax and Henry Wilson suggests that the work was not completed until 1870. Although dated to the late 1850s, the autographs of the two politicians were actually sewn under that of the 18th President, Ulysses S. Grant (1869-1877), to commemorate the most important office they held. It is believed that Adeline continued to work on the quilt for several years after she had obtained all the signatures.

An important public recognition came in 1864, when the writer and journalist Sarah Hale, whom Adeline had asked for her autograph to include in her quilt, dedicated words of praise to her in “Godey’s Lady’s Book,” the magazine she edited from 1837 to 1877. Hale returned to the subject four years later, in her book Manners; or, Happy Homes and Good Society, not hesitating to compare Harris’s quilt to the most important tapestry of medieval France:

«Who knows but that, in future ages, hes work may be looked at, like the Bayeux Tapestry, not only as a marvel of woman’s ingenious and intellectual industry, but as affording an idea of the civilization of our times, and also giving a notion of the persons as estimated in history?» 〈6〉.

Autograph signatures

As mentioned above, the quilt contains three hundred and sixty signatures of the personalities Adeline Harris most admired: a wide selection of the most important personalities of the 19th century, not only in the United States, divided into cultural and professional profiles 〈7〉. The space between the first and ninth columns contains mainly autographs of politicians, which are in turn divided into subcategories: the second and third columns include career military men such as John Charles Frémont and Ambrose Burnside; the seventh column contains eight presidents and two vice-presidents of the United States. The most prominent name is undoubtedly that of Abraham Lincoln, America’s 16th president.

The literary figures are the most numerous and are therefore divided into more specific sections. Firstly, there is the distinction by gender, which places female figures in the middle section of each line, from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century. These include Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), a seminal anti-slavery novel, and Julia Ward Howe, author of The Battle Hymn of the Republic (1861), a patriotic song still popular today. But there are also authors such as Ann Sophia Stephens, Caroline Gilman and Lydia Sigourney, who were famous when Harris made her quilt but have only recently been reappraised.

The ninth to twentieth columns are occupied by male authors, while the eleventh column is occupied by the most prominent American writers of the time, including Washington Irving, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. European authors such as Jacob Grimm, Alexandre Dumas, William Makepeace Thackeray and Charles Dickens stand out in the twelfth and thirteenth lines. Not infrequently, authors of the same literary genre – poets, novelists, humorists, publishers, historians, travel writers – can be found together.

The tenth column contains the names of major figures in science, including the German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt and the inventor of the telegraph, Samuel Morse.

In the arts, American artists such as painters Rembrandt Peale and Lilly Martin Spencer and sculptor Hiram Powers stand out in the thirteenth column.

Another important group of autographs is that of Protestant ministers: Episcopal bishops from many states, as well as Unitarian, Presbyterian, Universalist, Congregationalist and Baptist ministers. Prominent among them are names such as Henry Ward Beecher, pastor of Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, who was strongly opposed to the institution of slavery. The inclusion of such figures highlights not only the religious but also the socio-political orientations of Adeline and her family.

The last column of the quilt is dedicated to a number of teachers, including several professors at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, as well as at Yale, the university attended by Lorenzo Sears, Adeline’s future husband. The date 1859, coupled with one of the signatures, suggests that Adeline knew Sears (who graduated in 1861) several years before her marriage in 1866. Apparently, Adeline asked Lorenzo to list the names of some of the professors he liked, such as Latin teacher Thomas Thatcher, Sanskrit teacher William Dwight Whitney and Greek teacher James Hadley.

Many of the autographs were accompanied by dedications and mottos addressed to Adeline. The most curious of these compositions is the quatrain, which jokingly alludes to the quilt’s function as a bedspread and the number of names that adorned it:

«Miss Addie pray excuse

My disobliging Muse,

She Contemplates with dread

So many in a Bed» 〈8〉.

The text, in the lower right-hand corner of the quilt, had probably remained hidden for a long time, its playfully bold nature likely to cause embarrassment in the strict Protestant context of New England. It was specialists from the Metropolitan Museum who examined the quilt, which had recently come into the collection, and discovered a series of tiny holes caused by the sewing, later removed, of an additional patch of cloth intended to cover these very verses.

Posthumous events

Once completed, the quilt never left the family context and, in view of its excellent condition to this day, it is unlikely that it was ever used as a blanket or for any other purely practical purpose. It became a family heirloom, embodying Adeline’s intelligence and perseverance, and was handed down from generation to generation. Adeline left the quilt to her daughter Sophie, a philanthropist and director of the Providence Animal Rescue League. Sophie had no children from her marriage to George Howarth, but adopted his two daughters from a previous marriage. The quilt passed to the two girls, Amey Howarth Mackinney and Constance Howarth Kuhl, who in turn left it to their children. It was physically in the possession of Amey Howarth Mackinney, but shared with Harris’s other great-grandchildren when it was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1995 〈9〉. The work had a series of small rings sewn into the top, suggesting that it had once been hung upright, like a tapestry.

As well as providing a vivid historical and artistic record of the second half of the 19th century, Adeline’s Autograph Quilt has continued to provide valuable insights into later periods. Most recently, for example, it was chosen as the opening piece for In America, a Lexicon of Fashion, the exhibition that served as the backdrop for the 2021 edition of the Met Gala, the annual fundraiser for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute 〈10〉. In fact, it is now a symbol of women’s contribution to American civilisation and culture, and of the need to reaffirm their roles and privileges against all attempts at misrecognition.

Finally, like all Signature Quilts, but with a grandeur and intentionality that transcends the mere technical mode of execution, Adeline Harris’s anticipates one of the most recurrent aspects of contemporary art. And that is the relational, interpersonal dimension that presides over the creation of the work. A work that is realised through the involvement of an audience of people who are not seen as spectators but as co-authors, participants in a process that can be modulated in space and time.

〈1〉 For a profile of Adeline Harris, as gleaned from contemporary documents and the memoir written in the 1960s by her great-granddaughter Amey Howarth Mackinney, see A. Peck, "A Marvel of Woman's Ingenious and Intellectual Industry: The Adeline Harris Sears Autograph Quilt, "Metropolitan Museum Journal," v. 33, 1988, pp. 263-290. 〈2〉 See A. Peck, op. cit., p. 265. 〈3〉 An interesting case of Signature Quilt from England: R. Walsh, The Signature Quilt, "Goldsmiths Research Online," 2005. http://research.gold.ac.uk/2936/ 〈4〉 From the memoir of Amey Howarth Mackinney, quoted in A. Peck, op. cit., p. 267. 〈5〉 On the technical aspects of the Harris' quilt, in addition to A. Peck, op. cit., see E. Phipps, Technical Report on the Adeline Harris Sears Autograph Quilt, "Metropolitan Museum Journal," v. 33, 1988, pp. 291-295. 〈6〉 S. Hale, Manners; or, Happy Homes and Good Society All the Year Round, J.E. Tilton & Company, Boston 1868, p. 194. 〈7〉 For the complete inventory and index of signatures and inscriptions: A. Peck, op. cit. 〈8〉 Quoted in A. Peck, op. cit., p. 290. Peck dubiously attributes the quatrain to the journalist and poet Nathaniel Parker Willis, whose signature appears in the eighteenth of the twenty columns making up the quilt. 〈9〉 See Recent Acquisitions, A Selection: 1995–1996, "The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin", v. 54, no. 2, 1996, p. 50. 〈10〉 See A. Bolton, A. Garfinkel (eds.), In America: a Lexicon of Fashion, exhibition catalogue, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022. Homepage; Adeline Harris, Autograph Quilt (detail), third quarter 19th century, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art (photo © MMA). Below; Adeline Harris' quilt displayed in the exhibition "In America, a Lexicon of Fashion," New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Sept. 18, 2021-Sept. 15, 2022 (photo credits MMA).