by Antonia Tafuri, Roberta De Martino

On 11 June 1971, a considerable number of works by the artist Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach (Hadamar 1851 – Capri 1913) were donated to the Italian State by his heirs. Thirty-one paintings (thirty by Diefenbach and one by Ettore Ximenes, who portrayed the German artist) and five plaster sculptures found a worthy home in the Certosa di San Giacomo, thanks to Raffaello Causa, then Superintendent of the Historical Heritage of Campania. He understood the greatness of Diefenbach, not only as an artist but also as a reformer of life, calling him an «intense and lucid authentic artist»〈1〉. On September 12, 1974, the Diefenbach Museum, a new national museum and the first ever dedicated entirely to the German artist, reformist, pacifist, freethinker, symbolist, sun-worshipper and theosophist, was officially opened to the public. He was a sui generis personality for his way of understanding and facing life, for being against and outside the rules. «Erecting himself as a “pioneer of humanity,” he expressed in his artistic creations the ideas he preached» 〈2〉. As he himself wrote: «I regard art as a religion that must raise spirits to the beautiful and the good… The purpose of art must be exclusively moral» 〈3〉.

Often described to as a visionary painter, he did not want to be just a landscape painter, but saw art as preaching: «The artist must use his art as a means of expressing his ideas, as an educator leading humanity from earth to heaven. I try to achieve this in my art with all my strength. Each of my paintings is a sermon» 〈4〉. The tendencies of his mission as a man and as an artist are the liberation of humanity from the thousand miseries of the age, the «redemption of a culture informed by the most sublime divine humanism, freed from errors and lies, and based on the sure foundation of the laws of nature» 〈5〉.

Following the principles of the Lebensreform (the naturist movement that included Rudolf Steiner and Herman Hesse), Diefenbach decided to give up all luxury, chose a long white tunic and sandals for his feet, and began to preach in public about peace, love, universal brotherhood and a return to nature, in complete contrast to the industrialised and rearmed German society of the Wilhelmine era.

He arrived in Capri in December 1899, after a long journey that had taken him from the Alps first to Egypt and then to Trieste, and decided to live on the island until his death in 1913: «I chose Capri in order to build, with all my strength, a new existence on this marvellous island that could offer me the peace I so desired…» 〈6〉.

Here he had found his ideal dimension, dazzled by the mirage of a new, primitive norm of life, free from the many conventions of bourgeois society. The island, with its nature pervaded by a strong cosmic sense, had proved to be an inexhaustible source of inspiration, and the thirteen years of his stay were very dense for his creative activity, with the development of a new painting of great emotional impact, based on color modeled in relief with the addition of further materials. «Capri will be enough for me all my life with these rugged cliffs that I adore, with this tremendous and beautiful sea…» 〈7〉.

During the Capri period, the master also dabbled in sculpture, producing several plaster works: busts of his parents, a self-portrait, and two full-length statues of ephebes.

The half-length portraits of his father, Leonhard Diefenbach, and his mother, Therese Wolfermann, show a meticulous attention to expressive features and a delicate modelling. The works exhibited in the Casa Grande (the name given to the house-studio where Diefenbach lived from 1906, near the Piazzetta) must have been of particular consolation to the artist. In the bust-self-portrait, Diefenbach depicts himself as a young man, shirtless, reflecting his ideals of life through a more realistic modelling.

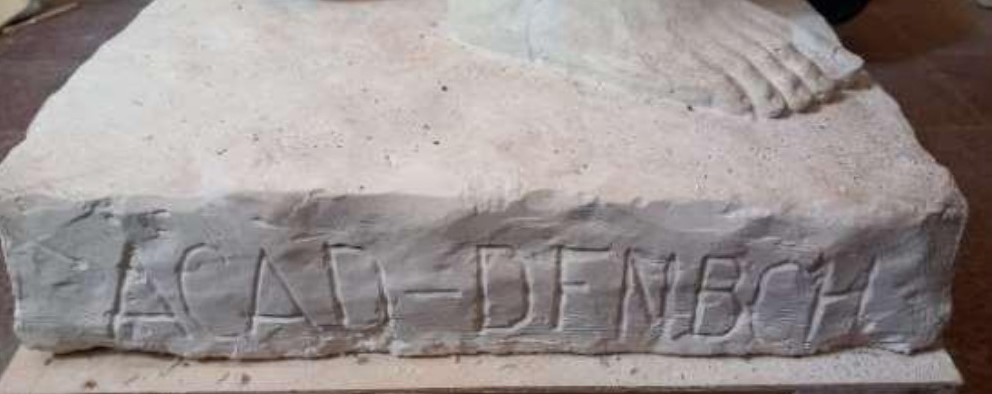

In the full-length statues of two Ephebes, the master embraces the classical aesthetic ideal that the natural grace of the naked human body is the highest expression of beauty. The balanced posture of the bodies reveals the search for balance, perfection and harmony. These creations are characterised by a formal classicism of intense idealisation, aimed at recovering the serenity and rigorous plasticity of the classics, and testify to an education based primarily on drawing and the study of classical sculpture, acquired during his training at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich 〈8〉, as evidenced by the inscription ACAD-DFNBCH placed at the base of both sculptures.

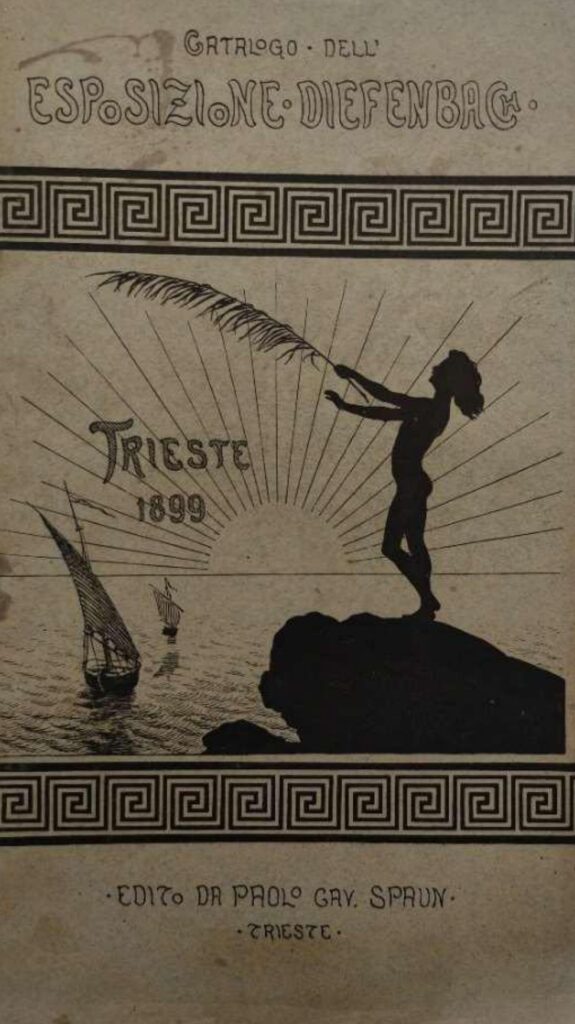

The first ephebe is shown with his arms raised. His right hand must be holding a palm tree, as shown by the figure already drawn on the cover of the 1899 Diefenbach exhibition catalogue in Trieste〈9〉. In fact, the silhouette of the young boy is depicted on a rock, in the act of holding up a palm tree with his right hand. In the background are the sea, two boats and the sun.

The artist often depicted the palm tree, attributing to it an important symbolic value that went far beyond its Christian meaning. The sacredness of the palm tree has ancient origins. In Greek mythology it is a plant of the sun, sacred to Apollo. In secular themes, the mythical figure of Victory appears in the act of presenting a palm branch to the victor. It was seen as a link between the earthly and the divine. The palm tree is also a symbol of the union of male and female: the trunk is reminiscent of the phallus, while the leaves and their fruits represent femininity. In the palm tree, sun, moon and fire are united: the rays recall the star of the day, the leaves the lunar cycle, and the fire because it is related to the mythical bird that rises from its ashes, the Arabian phoenix, as it is the first plant to be able to “re-grow” after a fire. The palm tree becomes a symbol of Christ’s conquest of death, the victory over sin and the triumph of peace 〈10〉.

The painter had arrived in Trieste in February 1899, «deprived of all the means of subsistence, involved in a battle of creditors with all his possessions and many of his paintings, evicted without any possibility of finding another place to live; shackled by the curatorship provisionally declared against him, and in danger of losing his personal freedom and his beloved children; shunned by “cultured” society; persecuted by the authorities; ridiculed by the press; insulted and targeted by the street plebs – a shameful picture of the life of the humanitarian and artistic spirit of Vienna! – Diefenbach left New Babel and, penniless, came to Trieste, from where he sought refuge in a secluded asylum, where he could finally find solace from his suffering and the peace to create new works. He is like a shipwrecked man thrown on the beach who has saved nothing but his own life!»〈11〉.

Here, in the far reaches of the Austrian Empire, the artist brought his children, the young student Paul von Spaun and Mina Vogler, his nurse and personal secretary. In Trieste, despite the widespread vilification in the Viennese press, he managed to win the respect of the city and its citizens through his works. The Trieste Art Circle supported him and allowed him to use the great hall of the old stock exchange as an atelier and exhibition space. Here, with the help of Paul von Spaun, Diefenbach tried to hold the last exhibition in the Austrian capital, which was inaugurated on 11 March 1899 and was so successful that he stayed in Trieste until the autumn of that year. Thus, in his works, the tragic allegories of his harsh destiny stand side by side with the sweet poetry of the childlike life of a humanity rejuvenated in its spirit.

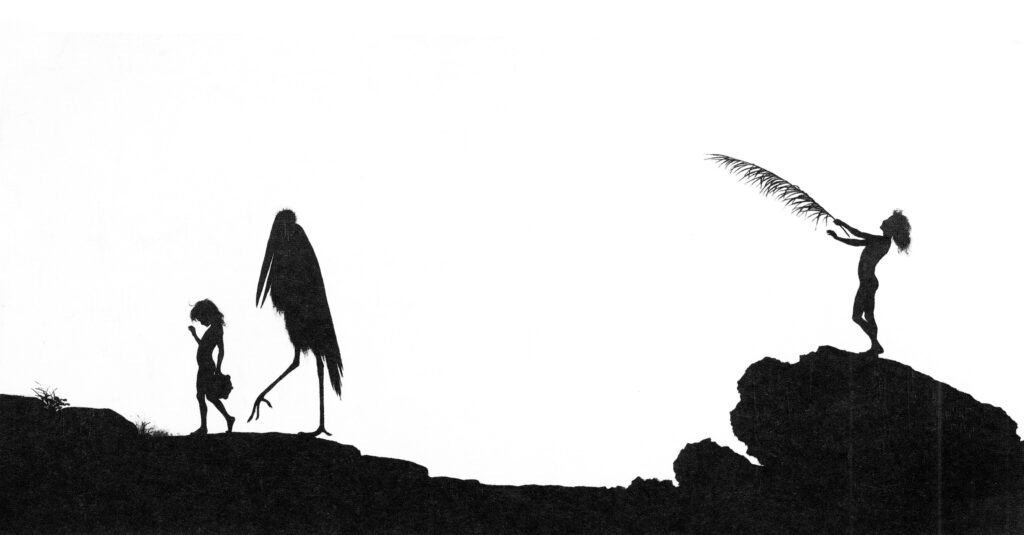

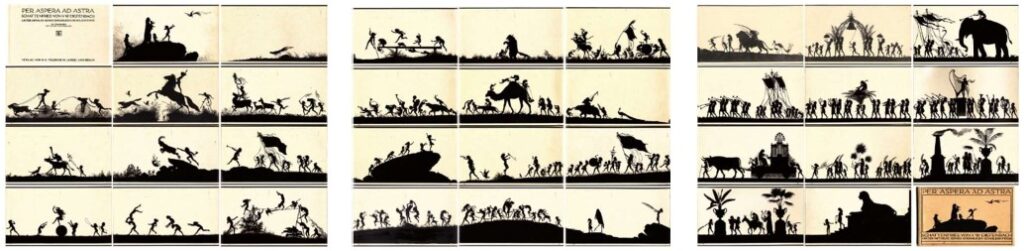

The ephebe, shown holding a palm tree, appears in a detail of the frieze Per aspera ad astra, the German artist’s most important work, considered a manifesto of Lebensreform and his spiritual testament. In the poetic text that accompanies the silhouettes, the artist describes the “fable of life”, his personal belief in the hope of reaching the longed-for land of the sun. The subtitle Meines Lebens Traum und Bild (“My Life’s Dream and Image”) makes it clear that the work was also meant to represent the story of the master’s own life, the autobiography of a man who, shattered by the gigantic struggle of his past life, sees before him the goal of his ambition: the entrance to the happy land, the laughing Eden.

The silhouette technique, already established in the 18th century, was revived by the artist at the end of the 19th century, at a time when precise and detailed photographic reproduction was preferred. The choice of silhouette and the master’s preference for black figures on a white background suited his message and allowed him to depict nudity in an innocent way.

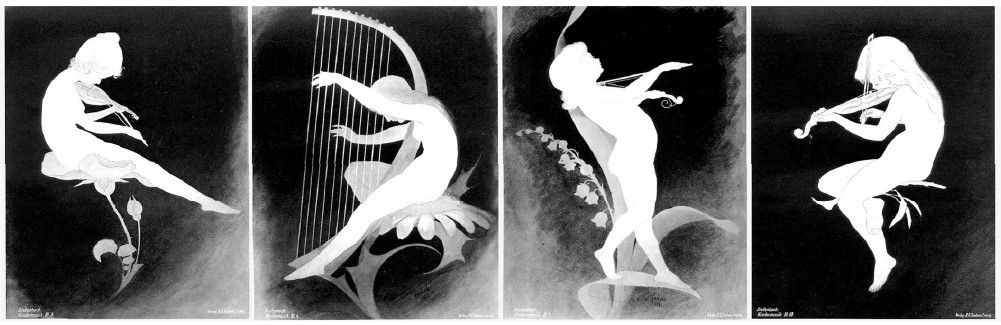

Kindermusik was Diefenbach’s first series of silhouettes; thirty sheets drawn in chalk and charcoal, the white figures on a black background emphasising the slight contours of the bodies. The series was begun by the young Diefenbach in Munich to ease the pain of his sick mother, and was completed during his stay in Höllriegelskreuth between 1881 and 1886.〈12〉. This is how Hugo Höppener (Lübeck, 1868 – Woltersdorf, 1948), Diefenbach’s most loyal pupil, so much so that he earned the nickname Fidus, described the work: «When I went to Diefenbach in the summer of 1887, I saw the Kindermusik, a wonderful series of childlike figures, playing and dancing, already almost finished, just waiting for the final touch. I saw something extraordinary and yet so spontaneous, a deep inner call. The figures were poetic images in which the primitive musical power of Böcklin, the pure grace of Schwind, and the simplicity and stylistic elegance of the Pre-Raphaelites were harmoniously combined […] I can find no comparison with this work, which, first of all, was able to express the new spirit through a conscious beauty of form, in a serene and optimistic style…» 〈13〉.

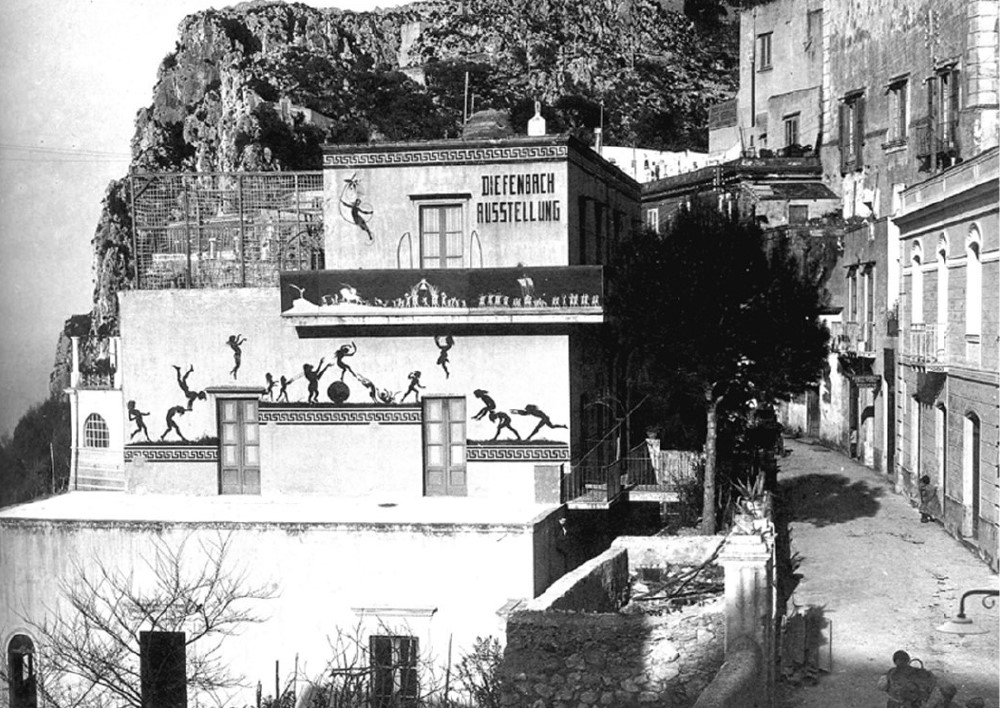

With the help of Fidus, Diefenbach then decided to use the drawings of Kindermusik to create a long frieze that would give a broader idea of his life’s journey: thus was born the masterpiece Per Aspera ad Astra, a monumental 68-metre long work created in Höllriegelskreuth in 1888. Diefenbach created this work in response to the sad moment when he was separated from his children. The work, which was followed by the publication of the “fable” in which the author narrated the ideal life of redeemed humanity depicted in the frieze, was later exhibited in Vienna in 1898 and was a great success. The artist took the silhouette technique and transferred it to oil on canvas, creating a painting of gigantic dimensions, an extraordinary masterpiece for its time; no fewer than thirty-four individual panels, each measuring 100 x 200 cm., which was donated to the Hadamar Municipal Museum in 1988. A second version of the same frieze was made to decorate the exterior of his house in Capri, of which unfortunately no trace remains.

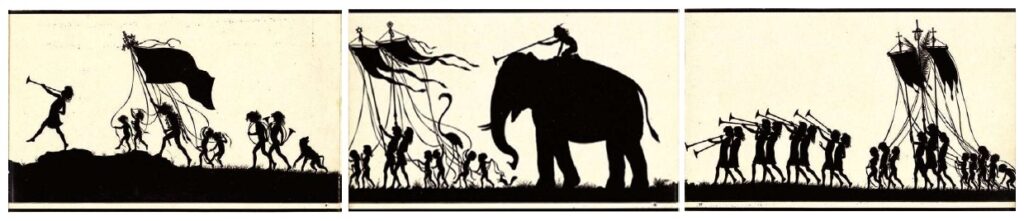

The protagonists of the “fable” are Diefenbach, his sons and Fidus, in search of this realm of peace and love. Through his experience, he wanted to convey an optimistic message to humanity: the journey ad astra required great sacrifices, but it was possible for man, according to theosophical ideas. In front of the protagonists is the path to God, populated by a host of carefree children and animals. The dancing, playful figures and the many animals are shown in a “parade of joie de vivre“, in a state of cheerful nudity, in a riot of movements that praise music, dance and play. Naked figures, young, slender, healthy and strong bodies move in unspoilt nature. Playfully dancing figures, regardless of gender and free from conventional constraints, move caressed by the elemental forces of nature: light, air and sun.

Tympani, fifes and trumpets herald the arrival of spring; harps and bells invite us to dance and circle; the pageantry of the heavenly procession becomes ever more solemn, and the harmonious sound of instruments of all kinds, produced in divine harmony by young maidens and children animated by noble enthusiasm, echoes ever louder. The masterpiece Per Aspera ad Astra can thus be seen as a manifesto of the ideals pursued by the Master: the culture of nudity, childlike naturalness, dress reform, vegetarianism and pacifism, which would allow man to enter an earthly paradise in harmony with nature.

A message of peace echoes throughout the frieze, reflecting Diefenbach’s struggle against war in support of the pacifism he pursued throughout his life 〈14〉. Some silhouettes play the salpinx, held in one hand. The salpinx is a reedless metal aerophone with a single reed, usually straight and ending in a bell, whose length could vary from eighty to one hundred and twenty centimetres, and was one of the main wind instruments used by the Greeks. Its powerful, ringing sound makes it an ideal instrument for open spaces and large crowds: in fact, it emits sounds of great intensity, making it possible to transmit signals over long distances. According to Greek writers, the salpinx was characterised by the sheer terror it instilled in its listeners in times of war. 〈15〉. The salpinx is used by Diefenbach not for battle, but to proclaim the sacred peace according to the Master’s message: «You must not kill! Stop the slaughter of men and animals! Peace on earth! For men and animals, holy peace for all of nature!» 〈16〉.

A study of the frieze, and in particular of the poses and instruments depicted in it, leads to the hypothesis that the other Ephebe, depicted with her right leg in front, her right arm raised, her palm facing upwards and her cheeks puffed out to produce the sound, was probably playing the salpinx.

〈1〉 R. Causa, Un nuovo museo: Diefenbach alla Certosa, “Nferta napoletana”, 1975, p. 14. 〈2〉 A. Tafuri, R. De Martino, Diefenbach e Capri, Grimaldi & C. Editori, Naples 2013, p. 9. 〈3〉 Testamento, Capri, july-august 1909, Diario n 27. 〈4,5〉 Quoted in P. von Spaun, Catalogue of the Diefenbach Exhibition, Trieste 1899, pp. 14 and 12. 〈6〉 Testamento, Capri, july-august 1909, Diario n. 27. 〈7〉 Quoted in E. Petraccone, Un artista d’eccezione, “Emporium”, n. 229, january 1914, p. 295. 〈8〉 See A. Tafuri, R. De Martino, op. cit., p. 86. 〈9〉 See P. von Spaun, op. cit., p. 12. 〈10〉 See G. Teresi, Il simbolismo della palma e delle sue radici, “Il pensiero mediterraneo”, 7 agosto 2022 www.ilpensieromediterraneo.it/il-simbolismo-della-palma-e-delle-sue-radici-de-metaphora-palmae-et-radicis-eius/11 〈11〉 P. von Spaun, op. cit., p. 12. 〈12〉 See A. Tafuri, R. De Martino, op. cit., pp. 59-61. 〈13〉 Quoted in M.P. Maino, M. Chiaretti (ed.), Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach (Hadamar 1851-Capri 1913), catalogo della mostra, Galleria dell’Emporio Floreale, Rome 1979, pag. 52. 〈14〉 See A. Tafuri, R. De Martino, op. cit., pp. 63-69. 〈15〉 See F. Berlinzani, Strumenti musicali e fonti letterarie, “Aristonothos. Rivista di Studi sul Mediterraneo Antico”, 2010, pp. 11-109. 〈16〉 K. W. Diefenbach, Per Aspera ad Astra. Capri 1900. La follia è un’isola, La Conchiglia, Capri 1989, pag. 65. BIBLIOGRAPHY • P. von Spaun, Catalogo della Esposizione Diefenbach, Trieste 1899. • K.W. Diefenbach, Diefenbach Ausstellung. Villa Camerelle. Capri 1903, Tipografia Sangiovanni Ventaglieri, Napoli 1903. • E. Petraccone, Un artista d’eccezione: K.W. Diefenbach, “Emporium”, n 229, january 1914. • L. Insabato, Un grande pittore dimenticato, a Capri: Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach, note estetiche e psicopatologiche, “Rivista di Patologia nervosa e mentale”, Siena 1954. • A. Ciccaglione, Ritorna a nuova vita a Capri il complesso della Certosa, “Roma”, september 13, 1974. • R. Causa, Un nuovo museo: Diefenbach alla Certosa, “Nferta napoletana”, 1975. • M.P. Maino, M. Chiaretti (ed.), Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach (Hadamar 1851 Capri 1913), exhibition catalogue, Roma, Galleria dell’Emporio Floreale, 1979. • F. De Coltana, Dalla luce la luce. Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach e l’esperienza della pittura, “Gran Bazar”, december 1983. • S. Todisco, K.W. Diefenbach. Omnia vincit ars. Omnia vincit ars, Electa, Naples 1988. • K.W. Diefenbach, Per aspera ad astra. Capri 1900. La follia è un’isola, La Conchiglia, Naples 1989. • G. Alisio (ed.), Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach 1851-1913. Dipinti da collezioni private, exhibition catalogue, Capri, Certosa di San Giacomo, 1995. • J. Frecot, J.F. Geist, D. Kerbs, Fidus. 1868-1948. Zur ästhetischen Praxis bürgerlicher Fluchtbewegungen, Rogner & Bernhard, Hamburg 1997. • M. Schiano, Manuela: Alla ricerca della Sonnenland: la missione di Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach, "Heliopolis", n 1, september-december 2002. • M. Schiano, Una stanza chiamata museo, “Nuova Museologia”, n 7, dicembre 2002. • M. Schiano, Conoscere Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach, “Conoscere Capri”, n 7, 2008. • M. Buhrs, C. Wagner, Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach (1851-1913) Lieber sterben, als meine ideale verleugnen!, exhibition catalogue, Munich, Villa Stuck, 2009. • A. Tafuri, R. De Martino, Diefenbach e Capri, Grimaldi & C., Naples 2013. Homepage and below; Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach, Per Aspera ad Astra, two silhouettes (Wikimedia).