by Karl Blossfeldt, Karl Nierendorf

Decorative iconographies have always drawn on phytomorphic motifs. Just think of the stylizations of the lotus and palm found in the ornamental arrangements of many cultures, or the acanthus leaves adorning capitals in the Corinthian order, or the ivy carved into medieval stone artifacts. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, after Art Nouveau had again drawn attention to the subject, photography also played an important role, highlighting the parallels existing between plant structure and human artifacts. A place of its own in botanical subject photography belongs to the collection signed in 1928 by German photographer Karl Blossfeldt under the title Urformen der Kunst. The images (120 plates in total, containing a selection from thousands of photographs taken by the author) were first published in volume that year. Author of the introductory text was Karl Nierendorf, owner of the Berlin gallery where Blossfeldt had exhibited his work in 1926. In 1929, Urformen der Kunst was published in English under the title Art Forms in Nature. Sculptor, lecturer and photographer, first a student, then a teacher at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Berlin, the German Karl Blossfeldt (1865-1932) had specialized, alongside his teacher Moritz Meurer, in metalworking techniques. A self-taught photographer, he adopted an extremely sharp and close focus to minutely analyze the structures of the plant world and make them transferable to the field of graphics and modeling. Urformen der Kunst was followed four years later, in 1932, by a second collection of photographies, Wundergarten der Natur, while a third, Wunder in der Natur, came out posthumously in 1942. Exhibitions and books made Blossfeldt an influential figure in the Neue Sachlichkeit, the artistic trend most in vogue in Germany in the 1920s and early 1930s, at the time of the Weimar Republic. Karl Nierendorf (1889-1947) was a gallery owner, financier and publisher active between Cologne and Berlin, where he played an important role in marketing the works of masters such as Dix, Kandinsky and Klee. In 1937 he emigrated to the United States, continuing his gallery activities there. Upon his death, the artworks he owned, including as many as 150 signed by Paul Klee, were acquired by the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Nierendorf's text we publish here is a visionary, almost mystical counterpoint to Blossfeldt's photographs, with their contrasting black and white, mindful of Renaissance woodcuts and chisels. Echoed in it are certain themes typical of the neo-pagan imagery that was widespread in the years between the two world wars; the cult of nature, body and sporting activity, and unlimited faith in technical progress. See K. Nierendorf, Art Forms in Nature, in K. Blossfeldt, Art Forms in Nature, Zwemmer, London 1929, pp. III-VIII.

Art and Nature, the two great manifestations in the world surrounding us, are so intimately related to one another that it is impossible to think of one without the other, and thus we can never compress them into a formula representing one idea. Infinitely multifarious as the realm of the crystalline, animal and vegetable forms which grow and perish with us may be, they are governed by a rigid and eternal law emanating from beyond this earth, and obey the profoundly mysterious Fiat of creation that called them into existence. For thousands of years every form in Nature has been a constant repetition of the same process, subject only to alterations due to climatic changes or the varying character of the soil, which do not interfere with their original shape. The fern and the horsetail already had their present form in inconceivably remote ages. Their size alone has undergone alterations through the development of the atmosphere of this planet.

It is the result of the creative act that distinguishes the works of Art from those of Nature, namely, the modelling of an original form, newly produced, and not the imitated or repeated form. Art has its immediate origin in the latest powerful incentive existing at the time, the most visible expression of which it is. In the same way that time has no part in the existence of a blade of grass which, being a symbol of everlasting primeval laws governing all life, appears monumental and worthy of veneration, so a work of Art has an overwhelmingly moving effect through its very uniqueness as the most concentrated manifestation, as an arc of light joining the two poles of the Past and the Future. From the Assyrian temple to the stadium of the present day, from the Buddha absorbed in meditation to The Thinker of Rodin, from the Chinese coloured wood-engraving to the modern copper-plate, everything created by man records the spirit of his epoch with such distinctiveness that it is easy to deduce from it the actual date of the creation. In the artistic production of every generation its relation to Nature, as well as to God and the science of mathematics, is revealed as in an open book. And the more securely the actual present is enshrined in a work the greater will be its value for eternity.

If man in the space of thousands of years would produce the same style of architecture and the same form of Art without variation, his creations would resemble the structures erected by bees and ants – merely products of Nature founded on parallel lines with the complicated nests of many birds, the web of a spider and the shell of a snail. But what exalts man above the other creatures is his capability of transformation by aid of his own spiritual force, which gave the Catholic of the Middle Ages and his entire world a totally different idea of building than, for instance, the Greek of classical times. As Nature, in its endless monotony of origin and decay, is the embodiment of a profoundly sublime secret, so Art is an equally incomprehensible second creation, emanating organically from the human heart and the human brain; a creation which from the very beginning of time and throughout the ages has had its origin in the yearning for perpetuity, for eternity, and in the desire to retain the spiritual face of its generation – doomed to be engulfed in the whirlpool of time – in stone, bronze, wood and painted forms that are independent of birth and death.

This may be said of mankind of the present day, as well as of any other period. We are witnesses of the fact that modern youth is rising up in revolt against merciless materialism and intellect ualism, dictated by the rapid progress of our time, and is returning to Nature with elemental vigour. Sport, a powerful manifestation common to every country on earth, here provides the necessary compensation. A new type of man appears – a free being, rejoicing in healthy exercise, intimately acquainted witli the elements air and water, tanned by the sun, and resolved to open out for himself a new and brighter world. The blessed and health-giving powers of light, air and sunshine are hilly recognised by him. His chief aim is the penetration of his body by the rays of the sun, the illumination of his whole being, and the transformation of all the various phases of life; in other words, he aims at active and immediate union with Nature. Simultaneously, a new form of architecture supersedes the dark stone caverns and opens out wide vistas by means of light walls of glass and actually brings the house and the garden together, the fantastic wealth of variety in the latter being made possible by the production of new species of flowers and their scientific cultivation. And, again, beyond the garden, the motor-car annihilates space between the town and the country.

With the aid of slow motion and rapid projection we can study in films the expansion and contraction, the breathing and the growth of plants. The microscope reveals systems of worlds in a single drop of water, and the instruments of the astronomical observatory enable us to explore the infinite depths of the universe. Modern technics bring us into closer touch with Nature than was ever possible before, and with the aid of scientific appliances we obtain glimpses into worlds which hitherto had been hidden from our senses. And it is technics also that provide us with new took for artistic moulding. Although the expression, “The battles of the spirit are fought out on canvas”, was justified in the 19 th century, the highest Art of which was its paintings, to-day the fight is waged with iron, concrete, steel, and so forth, and with the waves of light and ether. Our architecture, mechanical buildings, motor-cars, aeroplanes, as well as the film, the radio and photography, embrace possibilities of a high artistic order, and a thousand signs indicate that the triumph of technics, so often deplored, is not the victory of matter but the creative spirit manifesting itself in new forms.

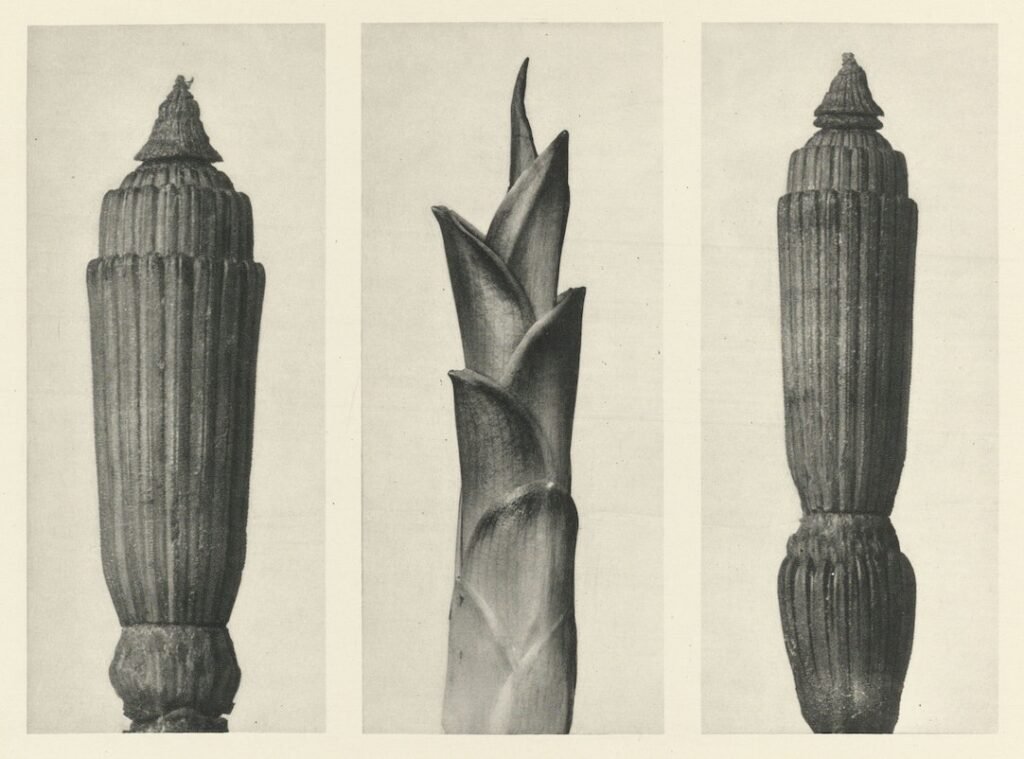

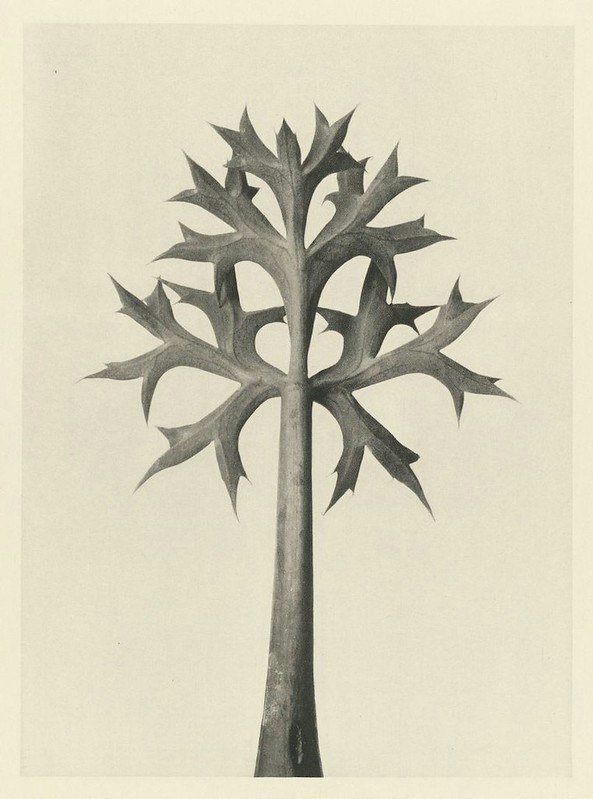

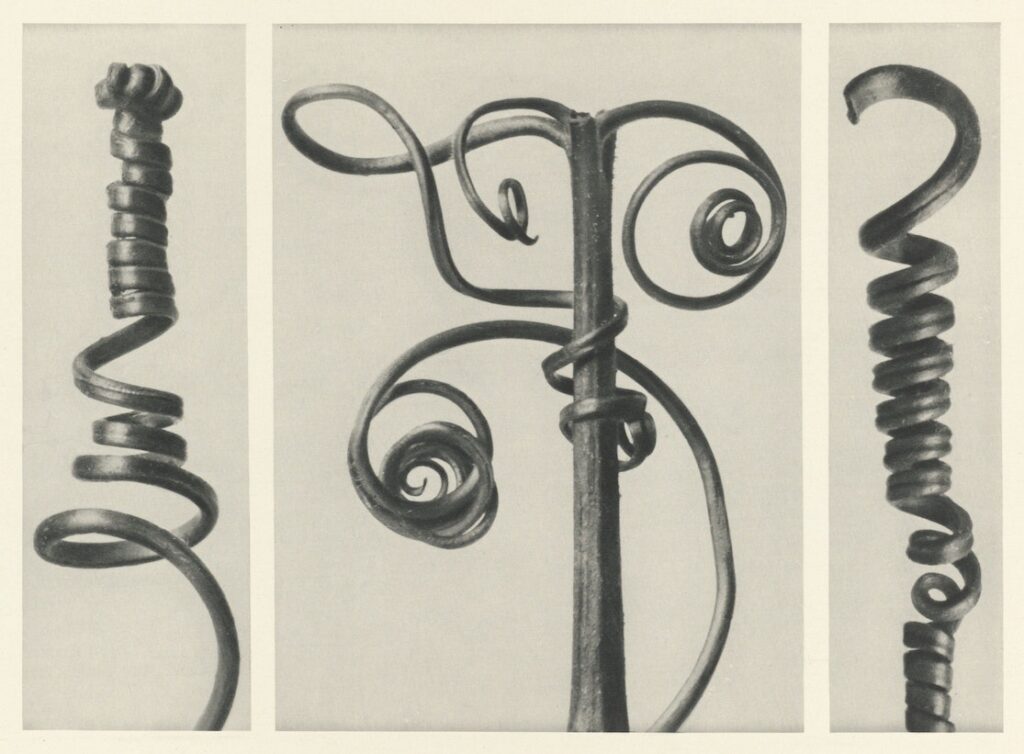

Thus, it is not by chance that a work is published now, which, with the aid of the photographic camera, by giving enlargements of certain parts of a plant, reveals the relationship existing between Art and Nature, never heretofore represented with such startling clearness. Professor Blossfeldt, architect and teacher at the United State Schools of Free and Applied Art in Berlin, in hundreds of photographic pictures of plants, which have not been retouched or artificially manipulated, but solely enlarged in different degrees, has demonstrated the close connection between the form produced by man and that developed by Nature.

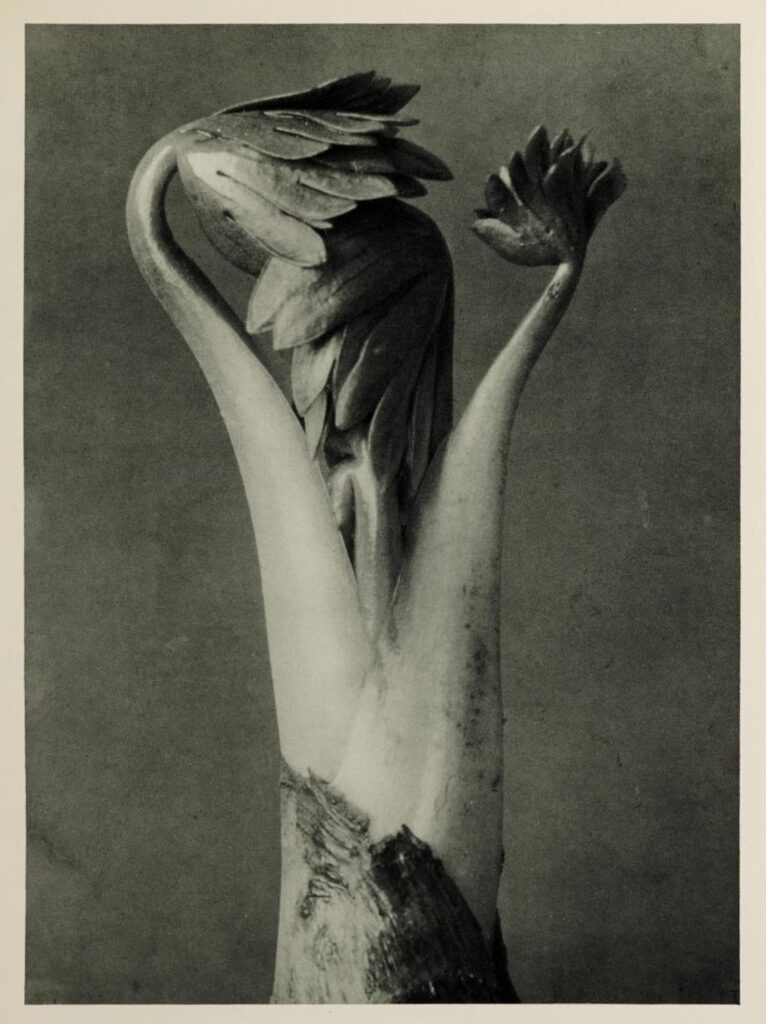

The following selection comprises 120 Plates from this rich material, and each reveals the unity of the Creative Will in Nature and in Art, proving this to be a fact by the positive evidence of the photographic plate and, therefore, all the more convincing. And as it was a person of eminence who recognised this fact as being his own peculiar task to develop and, consequently, adopted it as the aim of his life, there is unfolded to the artist who approaches Nature with the aid of the eye of the camera a world comprising all fo nns of past styles, from dramatic tension to austere repose, and even to the expression of lyrical and the most profound inspiration. The fickle delicacy of a Rococo ornament, as well as the heroic severity of a Renaissance chandelier, the mystically entangled tendrils of the Gothic flamboyant style, noble shafts of columns, cupolas and towers of exotic architecture, gilded episcopal crosiers, wrought-iron railings, precious sceptres, all these shapes and forms trace their original design to the plant world. Even the dance – a human body grown to art – finds its prototype in a bud, with its touchingly innocent movement and its expression of the purest psychic effort, a dream apparition descending from the realm of visions into the flowery regions of our terrestrial world. The picture of this small germinating sprout (PI. 96) bears witness with clear distinctness of the unity of the living and the moulded form, the dance, restricted to the ephemeral occurrence of the event in Nature, only becomes Art by the repetition ol motion as represented by the body, according to fixed rule and in strictly defined measures. It is called upon to wrest from the flood of development that movement to which it cannot bestow permanence, except by constant repetition; and whilst the bud of a plant continues to adopt that everlasting form which becomes for us the type of an animated body, in order later on to unfold itself, the dance perpetuates the psychic expression and thereby advances it to the time-accomplished atmosphere of Art.

Manifold are the phases of life and manifold, also, are the transformations undergone by man. Elevating in its joyousness, far beyond the aesthetic sensation, is the recognition that the hidden creative forces, to the fluctuations of which we, as beings created by Nature, are subject, are ruling everywhere with the same impartiality and authority in the works produced by each generation as a type of its existence, as well as in the most perishable and most delicate creations of Nature.

If the copperplate engravings in this work demonstrate distinctly for the first time the relations which become evident with increasing clearness, in the minute as well as in the great, they will contribute, on their part, to further the most important task that lies before us today, namely, to grasp the deeper meaning of our present time, which is striving for the recognition and realisation of a new unity in all spheres of Life, of Art and of Technics.

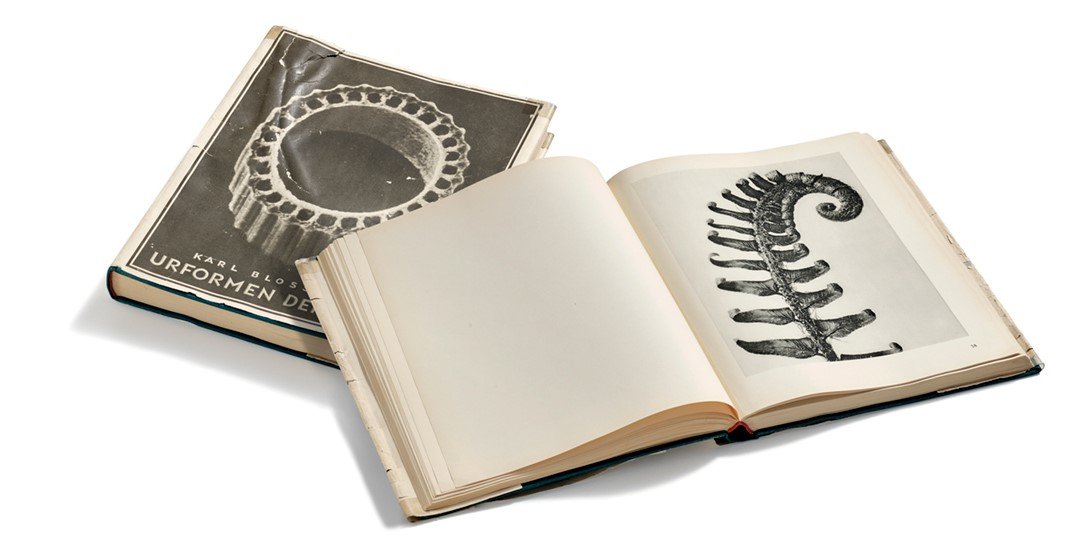

Homepage; Original edition of Karl Blossfeldt's book, "Urformen der Kunst", Galerie Nierendorf/Ernst Wasmuth Verlag, Berlin 1928.

Below; Karl Blossfeldt, Poppy Flower, a) enlarged 6 times, b) enlarged 10 times. Photographs reproduced in "Urformen der Kunst", plate 104 (publicdomainreview.org).