by Enrico Maria Davoli

Bibliography concerning sacred art and architecture in the contemporary age is extensive and constantly growing, on the impetus generated sixty years ago by the Second Vatican Council. The debate also attracts interest among the uninitiated, as witnessed by the controversies that arise whenever the liturgical adaptation of a place of worship, be it an illustrious monument or a minor reality known only to regular visitors, is undertaken. The proceedings of the conference Architettura e teologia nella costruzione di chiese, held on April 29, 2022 at the Faculty of Theology in Lugano, exemplify some very useful intellectual and professional positions in assessing the current state of the issue. Let us quickly review them.

A professor of canon law, in his opening remarks Arturo Cattaneo summarizes the essential requirements to which a church must respond, keeping himself equidistant from the very heterogeneous proposals on the table today.

Artist and art historian, Rodolfo Papa takes stock of the marriage of architecture and figurative arts in the Christian tradition, and thereby diagnoses a critical issue that, while ignored by the contemporary mainstream of the self-sufficient, self-signifying “author church,” is instead a sore point. That is: an architecture that is incapable of accommodating things and visions “other” than those put forth by the designer will a fortiori be incapable of accommodating the divine. Sacred art is indispensable to sacred architecture; the latter cannot be without the former.

A historian of architecture, Andrea Longhi seems to place himself in continuity with the previous position. However, his appeal to the church building as a collective creation, resulting from the interaction of many historical, cultural and social components, evades a basic question: how is it that, in a type of construction that more than any other aspires to embody instances of universality and perenniality, contemporary architectural design so often resolves itself into a soliloquy?

A historian of Christian art, Ralf van Bühren draws a synthesis of 20th- and 21st-century sacred architecture, but glosses over the period before the Second Vatican Council, as if that event had automatically dismissed of all validity all that had gone before. Grave underestimation this, if it is true that history does not die with those who make it; on the contrary, it lives on in the lessons that posterity can draw from it.

Finally, architects Paolo Zermani and Mario Botta evoke in exquisitely subjectivist terms (as is the status of today’s practicioner, free from constraints other than those of personal poetics) the salient stages of their careers in the sphere of the sacred.

What insights to draw from such a multifaceted landscape? We attempt here to formulate some, not necessarily in line with the findings of the Lugano conference. First, it is now clear that the experimentalist and neo-avant-garde strand of the second half of the twentieth century has had its day. This is not because its most precious pearls have lost their value, but because, in the incessant becoming of which they themselves are a part, they fail (as they never have succeeded) to exert that normative, guiding action that has always been proper to the masterpieces of every age. Let us take the best known and most admired of these pearls: the Chapelle de Ronchamp also mentioned several times in these proceedings. No one denies Le Corbusier’s building the license of masterpiece, let us be clear. The problem is another: like all works, however great, born of the radical deconstruction of a model-whether dolmen, temple, basilica-Ronchamp is inimitable in a literal, etymological sense. That is to say, not belonging to one architectural type, but adumbrating several without identifying with any, it cannot be the progenitor of any solution expendable in a context different from its origin: more prosaic, artistically less guarded, or simply not illuminated by that King Midas touch that is specific to its author. In short, an exception, however great, cannot turn into a rule. If anything, more exceptions will arise, the more paradoxical and an end in itself the more they try to imitate the inimitable, to approach the unapproachable. The contemporary history of church building in the hands of a few great architects and their epigones is just that: very few gems, and a myriad of trinkets that try in vain to vibrate with that light, to arouse that thrill. What is missing is an average, recognizable and sustainable level.

Where, then, should we look for examples of decorum-to use a key word from this magazine-compatible with the standards of the 2000s? In our opinion, in another 20th century: that is, in that first half of the 20th century, still alive and productive throughout the 1950s, which is being passed off today as a gray area, full of ambiguities to which it pays not to pay attention. Among the greats, the case of Auguste Perret (1874-1954) is illuminating: outclassed in popularity, notoriety and ideological expendability by his pupil Le Corbusier, he is usually dismissed as the terminal link in a chain that has now become too long. But it is precisely his attachment to archetypal forms, starting with the basilica, that allowed him great freedom and expressive authority, that made his spaces concrete and habitable (even by the works of other artists), even with the revival of the theory of architectural orders.

But let us dwell on Italy. Here, the first half of the twentieth century is an inexhaustible, and little-known, mine of solutions that explore the whole scholarly range of the sacred in architecture. The creation of new towns and villages, culminating during the Fascist regime (with all the historiographical totems and taboos that, on all sides, arose from the difficulty of confronting the artistic culture of the ventennio), offers rich deposits of pragmatic, anti-rhetorical modernity, filled with the priceless luxuries that are the truthful use of materials, the ornamental use of beams and bricks, the images embedded in the walls by mosaic, stained glass, majolica, fresco. The history of those decades is full of exciting experiences: rich even in the cheapness of materials, highly original even in the observance of archetypes.

If it is true that, as it is often said, beauty lies in the details, then archetypal forms, interpreted with the necessary dose of literalness, are an unparalleled test for church architecture. They exalt the talent of those who know how to vary on the theme and enhance its nuances; they dismantle egocentrisms, narcissisms, and personalisms; they promote civic, urban values, of which they are the materialization. In contrast, spectacular but extemporaneous inventions are functional to the immediate recognition of the work and the author, to the focus (especially in photographs intended for trade magazines and the media) of this or that salient feature. Where the salient feature may consist in making the symbol of the cross (reduced to an aniconic pattern) appear where one would least expect it, or in moving architectural forms and connections (domes, apses) as in a gigantic origami, moved by inextricable logic. The result of these exercises is to overthrow the symbol into esoteric apparition, the gymnastics of forms into exhibited culturism, thwarting the meaning of religious experience.

It seems that, at present, a substantial agnosticism pleases both the planners, who are free to indulge in mannerist mysticism, and the religious patrons, who – if they took a less neutral stance – would immediately be accused of being illiberal, autocratic, neo-absolutist, restorative, and so on. Perhaps the impasse could begin to unravel on both sides if some questions were asked. For example: when – as Zermani does by quoting medievalist Jacques Le Goff in the title of his talk – one calls the present age the “time of the merchants,” why not apply the same interpretive measure to other principals of architecture? Materialism for materialism’s sake, how is it that a large retail chain, or a multinational home-selling corporation, or a global fast food brand, give extremely precise directives to their designers, and their operating sites are recognizable and homogeneous at first glance? Why is it that Islamic finance is so liberal in commissioning our archistars to design the headquarters of museums, boutiques, and banks, while being intransigent about every detail when it comes to erecting mosques?

One will object: those ones work only for profit, those others do not even know what the separation of religious and secular power is. But then one realizes that the great world of merchants, of the West and the East, is hoarding stylistic features fine-tuned in the sphere of church architecture, and in so doing corroborates the sacredness and intangibility of its all-worldly mission. There is no trade fair pavilion or supermarket or private clinic that does not showcase the metal variant of the column-tree, branched at the top, that the whole world admires, in stone version, in Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia. And it is but one example. Might it not be time for the Church to return to actively attending to the imagery to which it has long given body and soul? This, too, is (materialistically speaking) a claim to be made.

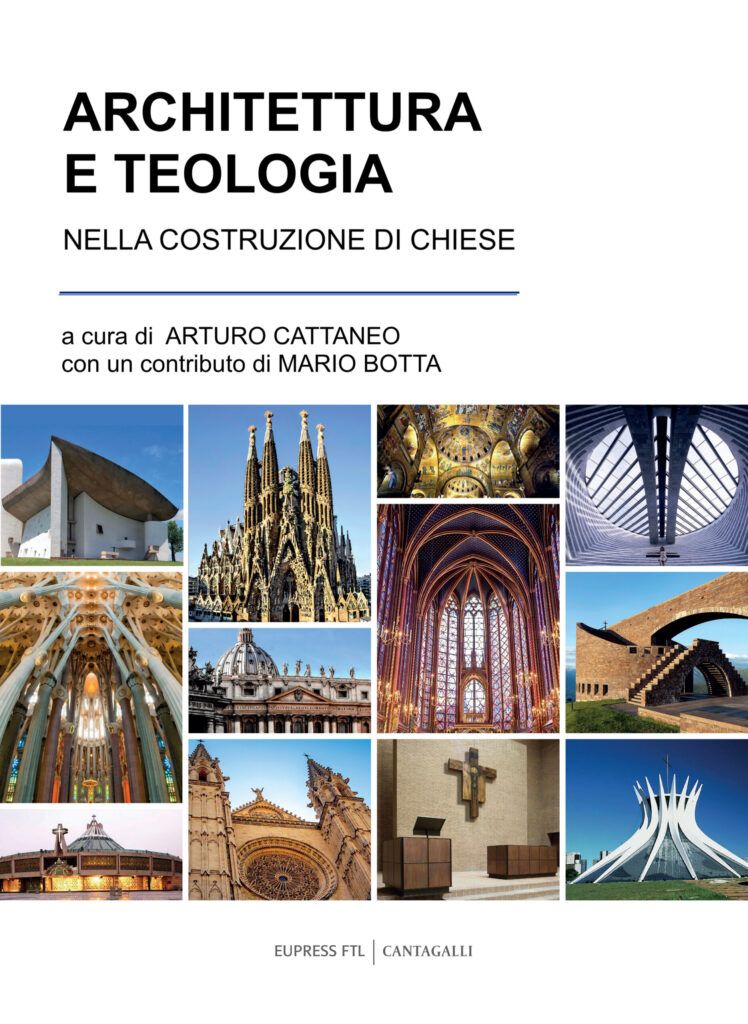

The book: Carlo Cattaneo (ed.), Architettura e teologia nella costruzione di chiese, Eupress-Cantagalli, Lugano-Siena 2023, pp. 170, euro 22.

Homepage; a view of the central square of Arsia (Raša), Croatia, with the church of St. Barbara (architect Gustavo Pulitzer Finali, 1936-37, photo © Paolo Mazzo). Below; the book cover.